What happens if my income changes and my premium subsidy is too big? Will I have to repay it?

Q: What happens if my income changes and my premium subsidy is too big? Will I have to repay it?

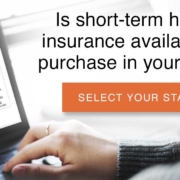

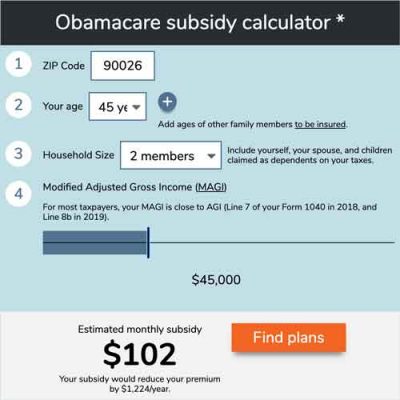

Use our calculator to estimate how much you could save on your ACA-compliant health insurance premiums.

A: Monthly premium subsidy amounts (ie, the advance premium tax credit – APTC – that’s paid to your insurer each month to offset the cost of your premium) are estimated based on prior-year income and projections for the year ahead, but the actual premium tax credit amount to which you’re entitled depends on your actual income in the year that you’re getting subsidized health insurance coverage.

If recipients end up earning more than anticipated, they could have to pay back some of the subsidy. This can catch people off guard, especially since the tax credits are paid directly to the insurance carriers each month, but if overpaid, they must be returned by the insureds themselves.

The issue of reconciling APTCs was explained in a 2013 IRS publication (see the final column on page 30383, continued on page 30384) which clearly explains that they do expect people to pay back subsidies that are in excess of the actual amount for which the household qualifies.

But the portion of an excess subsidy that must be repaid is capped for families with incomes up to 400 percent of federal poverty level (FPL). Details regarding the maximum amount that must be repaid, depending on income, are in the instructions for Form 8962, on Table 5 (Repayment Limitation). These amounts are adjusted annually, but for the 2020 tax year, the repayment caps range from $325 to $2,700, depending on your income and your tax filing status (single filer versus any other filing status). GOP lawmakers considered various proposals in 2017 that would have eliminated the repayment limitations, essentially requiring anyone who received excess APTC to pay back the full amount, regardless of income. But those proposals were not enacted.

There are some scenarios in which repayment caps do not apply:

- If a person projected an income below 400 percent of the poverty level (and received premium subsidies during the year based on that projection) but then ends up with an actual income above 400 percent of the poverty level (ie, not eligible for subsidies), the entire subsidy amount that was paid on their behalf has to be repaid to the IRS.

- If a person projected an income at or above 100 percent of the poverty level (and received premium subsidies) but then ends up with an income below the poverty level (ie, not eligible for subsidies), none of the subsidy has to be repaid. This is confirmed in the instructions for Form 8962, on page 8, in the section about Line 6 (Estimated household income at least 100% of the federal poverty line). But there are new rules as of 2019 that make it less likely for people with income below the poverty level to qualify for premium subsidies based on income projections that are above the poverty level. This is explained in more detail here.

Is there any help for me if I have to repay premium subsidies?

The IRS noted that they would “consider possible avenues of administrative relief” for tax filers who are struggling to pay back excess APTC, including such options as payment plans and the waiver of interest and penalties for people who must return subsidy over-payments. If you find yourself in a situation where you must pay back a significant amount of the premium subsidies you received during the prior year, contact the IRS to see if you can work out a favorable payment plan/interest arrangement.

It’s also worth noting that contributions to a pre-tax retirement account and/or a health savings account will reduce your ACA-specific modified adjusted gross income, which is what the IRS uses to determine your premium tax credit eligibility. If you had HSA-qualified health coverage during the year, you can make HSA contributions up until the tax filing deadline the following spring. And IRA contributions can also be made up until the tax filing deadline. You’ll want to talk with your tax advisor to see what makes the most sense given your specific circumstances, but you may find that some pre-tax savings end up making you eligible for a premium subsidy afterall, or reduce the amount that you’d otherwise have to repay.

The COVID pandemic caused widespread financial uncertainty and employment upheavals throughout much of 2020. Additional federal unemployment benefits were provided to millions of people, but there are concerns that the premium tax credit reconciliation could be particularly challenging during the 2021 tax filing season, with many people having to repay subsidies that were paid on their behalf during a time they were unemployed in 2020.

In December 2020, insurance commissioners from 11 states sent a letter to President-elect Biden, recommending various immediate and long-term actions designed to improve access to health coverage and care. One of the short-term recommendations is to provide relief from subsidy claw-backs for the 2020 tax year. Even in the best of times, it can be challenging to accurately project your income for the coming year, but the uncertainty caused by the COVID pandemic made this much more challenging than usual. So it’s possible that the Biden administration and/or Congress might be able to take action to provide some relief in this area, for at least the 2020 tax year.

What if you get employer-sponsored health insurance mid-year?

Most non-elderly Americans get their health coverage from an employer. Individual health insurance is great for filling in the gaps between jobs, but what happens if you start off the year without access to an affordable employer-sponsored health insurance plan, and then get a job mid-year that provides health coverage?

If a premium subsidy was paid on your behalf during the months you had individual market coverage, you may end up having to repay some or all of the subsidy when you file your tax return. It all depends on your total income for the year, including income from your new job. If your total income still ends up being in line with the estimate you provided when you applied for your subsidy, you won’t have to pay that money back. But if your actual income for the year ends up being substantially higher than you initially projected, you may end up having to repay some or all of that subsidy when you file your taxes.

It doesn’t matter that your income was lower when you were covered under the individual market plan. In the eyes of the IRS, annual income is annual income — it can be evenly distributed throughout the year, or come in the form of a windfall on December 31. (As noted above, insurance commissioners have urged the Biden administration to consider ways of providing relief on this issue for the 2020 tax year, given that it was even more challenging than normal to accurately project an annual income during the COVID panemic).

Once you become eligible for an affordable health insurance plan through your employer that provides minimum value, you’re no longer eligible for premium subsidies as of the month you become eligible for the employer’s plan. But premium tax credit reconciliation is done on a month-by-month basis, so as long as your total income for the year is still in the subsidy-eligible range, you’ll almost certainly still be eligible for at least some amount of subsidy for the months when you had a plan that you purchased through the exchange.

Finally, if you’re offered health insurance through an employer that you feel is too expensive based on the share you have to pay, you can’t just opt out, buy your own health plan, and attempt to snag a subsidy. The fact that an affordable plan (by IRS definitions) is available to you renders you ineligible for money toward your premiums. Unfortunately, the cost of obtaining family coverage is not taken into consideration when determining whether an employer-sponsored plan is affordable, which leaves some families stuck without a viable coverage option.

How many people have to repay premium subsidies?

For 2015 coverage, subsidies were reconciled when taxes were filed in early 2016. The IRS reported in early 2017 that about 3.3 million tax filers who received APTC in 2015 had to repay a portion of the subsidy when they filed their 2015 taxes; the average amount that had to be repaid was about $870, and 60 percent of people who had to pay back excess APTC still received a refund once the excess APTC was subtracted from their initial refund. [IRS data for premium tax credit reporting is available here; as of 2019, data had only been reported for the 2014 and 2015 tax years.]

But on the opposite end of the spectrum, about 2.4 million tax filers who were eligible for a premium tax credit ended up receiving all or some of it when they filed their return. These are people who either paid full price for their exchange plan in 2015 but ended up qualifying for a subsidy based on their 2015 income, or people who got an APTC that was less than the amount for which they ultimately qualified. The average amount of additional premium tax credit paid out on tax returns for 2015 was $670.

[The IRS noted that it was very uncommon for people to pay full price for their coverage and wait to claim their full refund on their return: 98 percent of the people who claimed a premium tax credit on their return had received at least some APTC during the year.]

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org. Her state health exchange updates are regularly cited by media who cover health reform and by other health insurance experts.

The post What happens if my income changes and my premium subsidy is too big? Will I have to repay it? appeared first on healthinsurance.org.