Open enrollment for health insurance plans in the individual market (on- and off-exchange) runs from November 1 to December 15 in most states. DC, California, and Colorado have extended open enrollment windows, and most of the other fully state-run exchanges generally extend their enrollment windows by at least a week each year.

Once open enrollment ends, ACA-compliant plans are only available to people who experience a qualifying event. The plans available outside of open enrollment without a qualifying event are not regulated by the ACA, and most are not a good choice to serve as stand-alone coverage (short-term health insurance is intended to serve as stand-alone coverage for a short period of time, but it’s much less robust than ACA-compliant coverage).

Qualifying events

Outside of open enrollment, you can still enroll in a new plan if you have a qualifying event that triggers your own special open enrollment (SEP) window.

People with employer-sponsored health insurance are used to both open enrollment windows and qualifying events. In the employer group market, plans have annual open enrollment times when members can make changes to their plans and eligible employees can enroll. Outside of that time frame, however, a qualifying event is required in order to enroll or change coverage.

In the individual market, this was never part of the equation prior to 2014 — people could apply for coverage anytime they wanted. But policies were not guaranteed issue, so pre-existing conditions meant that some people couldn’t get coverage or had to pay more for their policies.

All of that changed thanks to the ACA. Individual coverage is now quite similar to group coverage. As a result, the individual market now utilizes annual open enrollment windows and allows for special enrollment windows triggered by qualifying events.

So you could still have an opportunity to enroll in ACA-compliant coverage outside of the open enrollment window if you experience a qualifying event. Depending on the circumstances, you may have a special open enrollment period – generally 60 days but sometimes there’s an additional 60-day window before the event as well – during which you can enroll or switch to a different plan.

Got a qualifying event? You’ll need proof

It’s important to note that HHS began ramping up enforcement of special enrollment period eligibility in 2016, amid concerns that enforcement had previously been too lax.

In February 2016, HHS confirmed that they would begin requiring proof of eligibility in order to grant special enrollment periods triggered by birth/adoption/placement for adoption, a permanent move, loss of other coverage, and marriage (together, these account for three-quarters of all qualifying events in Healthcare.gov states).

The new SEP eligibility verification process was implemented in June 2016. In September 2016, HHS answered several frequently asked questions regarding the verification process for qualifying events, and noted that SEP enrollments since June were down about 15 percent below where they had been during the same time period in 2015 (after staying roughly even with 2015 numbers in the months prior to the implementation of the new eligibility verification process).

But HHS stopped short of issuing an explanation for the decline: it could be that people were previously enrolling who didn’t actually have a qualifying event, but it could also be that the process for enrolling had become more cumbersome due to the added verification step, deterring healthy enrollees from signing up. The vast majority of people who are eligible for SEPs do not enroll in coverage during the SEP, and this could simply have been heightened by the new eligibility verification process.

Nevertheless, the eligibility verification process was further stepped-up in 2017, thanks to “market stabilization” rules that HHS finalized in April 2017.

Starting in June 2017, HHS was planning to implement a pilot program to further enhance SEP eligibility verification (this plan was created by HHS under the Obama Administration). Fifty percent of SEP enrollees were to be randomly selected for the pilot program, and their enrollments would be pended until their verification documents were submitted. They’d have 30 days to submit their proof of SEP eligibility, and as long as they did so, their policy would be effective as of the date determined by the date of their application/plan selection (so for example, a person could enroll on July 10 for an August 1 effective date, but the enrollment would then be pended. If the applicant submitted proof of SEP eligibility on August 5, the enrollment would be completed, with coverage effective August 1).

Under the new rules finalized in April 2017, however, that SEP eligibility verification process began to apply to 100 percent of SEP applications, starting in June 2017. So if you’re planning to enroll in a HealthCare.gov plan outside of open enrollment, be prepared to provide proof of your qualifying event when you apply. Most of the state-run exchanges have followed suit, and HHS has proposed a requirement that state-run exchanges conduct SEP eligibility verification for at least 75 percent of all SEP applications by 2022.

The SEP verification program has generated controversy, with some consumer advocates noting that it could further deter healthy people from enrolling when they’re eligible for a SEP. At Health Affairs, Tim Jost suggested some alternative solutions, including a requirement that insurance carriers pay broker commissions for SEP enrollments in order to incentivize brokers to help more people enroll (at that point, insurers were increasingly paying no commissions for SEP enrollments, although many have started doing so in more recent years), and a requirement that group health plans provide certificates of creditable coverage to people losing their group coverage (this used to be required, but isn’t any longer; reinstating a requirement that the certificates be issued would make it easier for people to easily prove that they had lost coverage and had thus become eligible for a SEP).

But as a general rule, be prepared to provide proof of your qualifying event when you enroll.

Off-exchange special enrollment periods

Note that most qualifying events apply both inside and outside the exchanges. There are a few exceptions, however. For policies sold outside the exchanges, there are a few qualifying events that HHS does not require carriers to accept as triggers for special enrollment periods (however, the carriers can accept them if they wish). These include gaining citizenship or a lawful presence in the US or being a Native American (within the exchanges, Native Americans can make plan changes as often as once per month, and enrollment runs year-round).

In addition, when exchanges grant special enrollment periods based on “exceptional circumstances” those special enrollment periods apply within the exchanges; off-exchange, it’s up to the carriers as to whether or not they want to implement similar special enrollment periods.

And carriers tend to have fairly strict rules regarding proof of SEP eligibility. If you’re enrolling directly with an insurer, outside of open enrollment, you will need to provide proof of your qualifying event (the insurer will let you know what will count as acceptable documentation; these same documentation requirements are generally enforced for on-exchange enrollments as well).

What counts as a qualifying event?

Although special enrollment period windows are generally longer in the individual market, many of the same life events count as a qualifying event for employer-based plans and individual market plans. But some are specific to the individual market under Obamacare. [For reference, special enrollment period rules for employer-sponsored plans are detailed here; for individual market plans, they’re detailed here and described in more detail below and in our guide to special enrollment periods.]

When will coverage take effect if I enroll during a special enrollment period?

For most qualifying events, in states using HealthCare.gov and some of the state-run exchanges, applications completed by the 15th of the month will be given a first-of-the-following-month effective date.

Massachusetts and Rhode Island both allow enrollees to sign up as late as the 23rd of the month and have coverage effective the first of the following month.

Applications received from the 16th (or the 24th if you’re in MA or RI) to the end of the month will have an effective date of the first of the second following month. (Marriage, loss of other coverage, and birth/adoption have special effective date rules, described below.)

Starting in 2022, the federally-run marketplace (HealthCare.gov, which is used in 36 states as of 2021) will eliminate the requirement that applications be submitted by the 15th of the month in order to get coverage the first of the following month. For all special enrollment periods, coverage will simply take effect the first of the month after the application is submitted. States will have the option to require this of off-exchange insurers, and fully state-run exchanges will also have the option to switch all of their special enrollment periods to first-of-the-following-month effective dates, regardless of when the application is submitted.

Note that in early 2016, HHS eliminated some little-used special enrollment periods that were no longer necessary. For example, the special enrollment period that had previously been available for people whose Pre-Existing Conditions Health Insurance Program (PCIP) had ended; coverage under those plans ended in 2014; but there’s still a special enrollment period for anyone whose minimum essential coverage ends involuntarily).

12 special open enrollment triggers

The qualifying events that trigger special enrollment periods are discussed in more detail in our extensive guide devoted to qualifying events and special enrollment periods. But here’s a summary:

[Note that in most cases, the market stabilization regulations now prevent enrollees from using a special enrollment period to move up to a higher metal level of coverage; so if you have a bronze plan and move to a new area mid-year, for example, you would not be allowed to purchase a gold plan during your special enrollment period.]

Involuntary loss of other coverage

The coverage you’re losing has to be minimum essential coverage, and the loss has to be involuntary. Cancelling the plan or failing to pay the premiums does not count as involuntary loss, but voluntarily leaving a job and thus losing employer-sponsored health coverage does count as an involuntary loss of coverage. In most cases, loss of coverage that isn’t minimum essential coverage does not trigger a special open enrollment.

[There is an exception for pregnancy Medicaid, CHIP unborn child, and Medically Needy Medicaid: These types of coverage are not minimum essential coverage, but people who lose coverage under these plans do qualify for a special enrollment period (this includes a woman who has CHIP unborn child coverage for her baby during pregnancy, but no additional coverage for herself; she will qualify for a loss of coverage SEP for herself when the unborn child CHIP coverage ends). And although they are not technically considered minimum essential coverage, they do count as minimum essential prior coverage in the case of special enrollment periods that require a person to have previously had coverage (this is a requirement for most special enrollment periods).]

Your special open enrollment begins 60 days before the termination date, so it’s possible to get a new ACA-compliant plan with no gap in coverage, as long as your prior plan doesn’t end mid-month. (See details in Section (d)(6)(iii) the code of federal regulations 155.420, and the updated regulation that makes advance open enrollment possible for people with individual coverage as well as employer-sponsored coverage.) You also have 60 days after your plan ends during which you can select a new ACA-compliant plan.

If you enroll prior to the loss of coverage, the effective date is the first of the month following the loss of coverage, regardless of the date you enroll (ie, if your plan is ending June 30, you can enroll anytime in May or June and your new plan will be effective July 1). But if you enroll in the 60 days after your plan ends, the exchange can either allow a first-of-the-following-month effective date regardless of the date you enroll, or they can use their normal deadline, which is typically the 15th of the month in order to get a plan effective the first of the following month.

As noted above, starting in 2022, the federally-run marketplace (HealthCare.gov) will eliminate the requirement that enrollments be submitted by the 15th of the month to have coverage effective the first of the following month. So as of 2022, a person who loses coverage and enrolls in a new plan after the coverage loss will simply have coverage effective the first of the month after the enrollment is submitted.

Individual plan renewing outside of the regular open enrollment

HHS issued a regulation in late May 2014 that included a provision to allow a special open enrollment for people whose health plan is renewing — but not terminating — outside of regular open enrollment. Although ACA-compliant plans run on a calendar-year schedule, that is not always the case for grandmothered and grandfathered plans, nor is it always the case for employer-sponsored plans.

Insureds with these plans may accept the renewal but are not obligated to do so. Instead, they can select a new ACA-compliant plan during the 60 days prior to the renewal date and 60 days following the renewal date. Initially, this special enrollment period was intended to be used only in 2014, but in February 2015 HHS issued a final regulation that confirms this special enrollment period would be on-going. So it continues to apply to people who have grandfathered or grandmothered plans that renew outside of open enrollment each year. And HHS also confirmed that this SEP applies to people who have a non-calendar year group plan that’s renewing; they can keep that plan or switch to an individual market plan using an SEP. [Note that if the employer-sponsored plan is considered affordable and provides minimum value, the applicant is not eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange.]

Becoming a dependent or gaining a dependent

Becoming or gaining a dependent (as a result or birth, adoption, or placement in foster care) is a qualifying event. Coverage is back-dated to the date of birth, adoption, or placement in foster care (subsequent regulations also allow parents the option to select a later effective date). Because of the special rules regarding effective dates, it’s wise to use a special enrollment period in this case, even if the child is born or adopted during the general open enrollment period.

The current regulation states that anyone who “gains a dependent or becomes a dependent” is eligible for a special open enrollment window, which obviously includes both the parents and the new baby or newly adopted or fostered child. But HealthCare.gov accepts applications for the entire family (including siblings) during the special open enrollment window.

The market stabilization rule that HHS finalized in April 2017 added some new restrictions to this SEP: If a new parent is already enrolled in a QHP, he or she can add the baby/adopted child to the plan (or enroll with the new dependent in a plan at the same metal level, if for some reason the child cannot be added to the plan). Alternatively, the child can be enrolled on its own into any available plan. But the SEP cannot be used as an opportunity for the parent to switch plans and enroll in a new plan with the child. New rules issued in 2018 clarify that existing dependents do not have an independent SEP to enroll in new coverage separately from the person gaining a dependent or becoming a dependent. But they do state that an individual who gains a dependent “may enroll in or change coverage along with his or her dependents, including the newly-gained dependent(s) and any existing dependents.” That would seem to indicate that a new parent who already has individual market coverage does have the option to switch to a different plan using the SEP. As is the case with other SEPs, if you live in a state that is running its own exchange, check with your exchange to see how they have interpreted the regulations.

Marriage

If you get married, you have a 60-day open enrollment window that begins on your wedding day. However,

rules issued in 2017 limit this special enrollment period somewhat.

At least one partner must have had minimum essential coverage (or lived outside the U.S. or in a U.S. Territory) for at least one of the 60 days prior to the marriage. In other words, you cannot use marriage to gain coverage if neither of you had coverage before getting married.

Assuming you’re eligible for a special enrollment period (which includes providing proof of marriage), your policy will be effective the first of the month following your application, regardless of what date you complete your enrollment. Since marriage triggers a special effective date rule, it might make sense to use your special enrollment period if you get married during the general open enrollment period. For example, if you get married on November 27, you can select a new plan that day (or up until the 30th) and have coverage effective December 1 if you use your special enrollment period triggered by your marriage. But if you enroll under the general open enrollment period, your new coverage won’t be effective until January 1.

Divorce

If you lose your existing health insurance because of a divorce, you qualify for a special open enrollment based on the loss of coverage rule discussed above.

Exchanges also have the option of granting a special enrollment period for people who lose a dependent or lose dependent status as a result of a divorce or death, even if coverage is not lost as a result. This special enrollment period was due to become mandatory in all exchanges as of January 2017, but HHS

removed that requirement in May 2016, so it’s still optional for the exchanges. In most states, including the 36 states that use HealthCare.gov, divorce without an accompanying loss of coverage generally does not trigger a special enrollment period.

Becoming a United States citizen or lawfully present resident

This qualifying event only applies within the exchanges — carriers selling coverage off-exchange are not required to offer a special enrollment period for people who gain citizenship or lawful presence in the US.

A permanent move

This special enrollment period applies as long as you move to an area where different qualified health plans (QHPs) are available. This special enrollment period is only available to applicants who already had minimum essential coverage in force for at least one of the 60 days prior to the move (with exceptions for people moving back to the US from abroad, newly released from incarceration, or previously in the coverage gap in a state that did not expand Medicaid; there’s also an exemption for people who move from an area where there were no plans available in the exchange, although there have never been any areas without exchange plans).

For people who meet the prior coverage requirement, a permanent move to a new state will always trigger a special open enrollment period, because each state has its own health plans. But even a move within a state can be a qualifying event, as some states have QHPs that are only offered in certain regions of the state. So if you move to a part of the state that has plans that were not available in your old area, or if the plan you had before is not available in your new area, you’ll qualify for a special open enrollment period, assuming you had coverage prior to your move.

HHS finalized a provision in February 2015 that allows people advance access to a special enrollment period starting 60 days prior to a move, but this is optional for the exchanges. It was originally scheduled to be mandatory starting in January 2017 (ie, that exchanges would have to offer a special enrollment period in advance of a move), but HHS removed that deadline in May 2016, making it permanently optional for exchanges to allow people to report an impending move and enroll in a new health plan. If the exchange in your state offers that option, you can enroll in a new health plan on or before the date of your move and the new plan will be effective the first of the following month. If you enroll during the 60 days following the move, the effective date will follow the normal rules outlined above (ie, in most states, enrollments submitted by the 15th of the month will have first of the following month effective dates, although HealthCare.gov will remove this deadline as of 2022).

In early 2016, HHS clarified that moving to a hospital in another area for medical treatment does not constitute a permanent move, and would not make a person eligible for a special enrollment period. And a temporary move to a new location also does not trigger a special enrollment period. However, a person who has homes in more than one state (for example, a “snowbird” early retiree) can establish residency in both states, and can switch policies to coincide with a move between homes (HHS has noted that this person might be better served by a plan with a nationwide network in order to avoid resetting deductibles mid-year, but such plans are not available in many areas).

An error or problem with enrollment

If the enrollment error (or lack of enrollment, as the case may be) was the fault of the exchange, HHS, or an enrollment assister, a special enrollment period can be granted. In this case, the exchange can properly enroll the person (or allow them to change plans) outside of open enrollment in order to remedy the problem.

Employer-sponsored plan becomes unaffordable or stops providing minimum value

An employer-sponsored plan is considered affordable in 2021 as long the employee isn’t required to pay more than 9.83 percent of household income for just the employee’s portion of the coverage. And a plan provides minimum value as long as it covers at least 60 percent of expected costs for a standard population and also provides substantial coverage for inpatient and physician services.

A plan design change could result in a plan no longer providing minimum value. And there are a variety of situations that could result in a plan no longer being affordable, including a reduction in work hours (with the resulting pay cut meaning that the employee’s insurance takes up a larger share of their household income) or an increase in the premiums that the employee has to pay for their coverage.

In either scenario, a special enrollment period is available, during which the person can switch to an individual market plan instead. And premium subsidies are available in the exchange if the person’s employer-sponsored coverage doesn’t provide minimum value and/or isn’t affordable.

An income increase that moves you out of the coverage gap

There are 13 states where there is still a Medicaid coverage gap, and an estimated 2.3 million people are unable to access affordable health coverage as a result. (Wisconsin has not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, but does not have a coverage gap; Oklahoma and Missouri will expand Medicaid in mid-2021 and will no longer have coverage gaps at that point).

For people in the coverage gap, enrollment in full-price coverage is generally an unrealistic option. HHS recognized that, and allows a special enrollment period for these individuals if their income increases during the year to a level that makes them eligible for premium subsidies (ie, to at least the poverty level).

As mentioned above, the new market stabilization rules only allow a special enrollment period triggered by marriage if at least one partner already had minimum essential coverage before getting married. However, if two people in the coverage gap get married, their combined income may put their household above the poverty level, making them eligible for premium subsidies. In that case, they would have access to a special enrollment period despite the fact that neither of them had coverage prior to getting married.

Gaining access to a QSEHRA or Individual Coverage HRA

This is a new special enrollment period that became available in 2020, under the terms of the Trump Administrations’s new rules for health reimbursement arrangements that reimburse employees for individual market coverage. QSEHRAs became available in 2017 (as part of the 21st Century Cures Act) and allow small employers to reimburse employees for the cost of individual market coverage (up to limits imposed by the IRS). But prior to 2020, there was no special enrollment period for people who gained access to a QSEHRA.

As of 2020, the Trump administration’s new guidelines allow employers of any size to reimburse employees for the cost of individual market coverage. And the new rules also add a special enrollment period — listed at 45 CFR 155.420(d)(14) — for people who become eligible for a QSEHRA benefit or an Individual Coverage HRA benefit.

This includes people who are newly eligible for the benefit, as well as people who were offered the option in prior years but either didn’t take it or took it temporarily. In other words, anyone who is transitioning to QSEHRA or Individual Coverage HRA benefits — regardless of their prior coverage — has access to a special enrollment period during which they can select an individual market plan (or switch from their existing individual market plan to a different one), on-exchange or outside the exchange.

This special enrollment period is available starting 60 days before the QSEHRA or Individual Coverage HRA benefit takes effect, in order to allow people time to enroll in an individual market plan that will be effective on the day that the QSEHRA or Individual Coverage HRA takes effect.

An income or circumstance change that makes you newly eligible (or ineligible) for subsidies or CSR

If your income or circumstances change such that you become newly eligible or newly ineligible for premium tax credits or newly-eligible for cost-sharing subsidies, you’ll have an opportunity to switch plans. This rule already existed for people who were already enrolled in a plan through the exchange (and as noted above, for people in states that have not expanded Medicaid who experience a change in income that makes them eligible for subsidies in the exchange — even if they weren’t enrolled in any coverage at all prior to their income change).

But in the 2020 Benefit and Payment Parameters, HHS finalized a proposal to expand this special enrollment period to include people who are enrolled in off-exchange coverage (ie, without any subsidies, since subsidies aren’t available off-exchange), and who experience an income change that makes them newly-eligible for premium subsidies or cost-sharing subsidies.

This special enrollment period was added at 45 CFR 155.420(d)(6)(v), although it is optional for state-run exchanges. HealthCare.gov planned to make it available as of 2020, although there have been numerous reports from enrollment assisters indicating that it’s still difficult to access as of mid-2020. This is an important addition to the special enrollment period rules, particularly given the “silver switch” approach that many states have taken with regards to the loss of federal funding for cost-sharing reductions (CSR). In 2018 and 2019, people who opted for lower-cost off-exchange silver plans (that didn’t include the cost of CSR in their premiums) were stuck with those plans throughout the year, even if their income changed mid-year to a level that would have been subsidy-eligible. That’s because an income change was not a qualifying event unless you were already enrolled in a plan through the exchange (or moving out of the Medicaid coverage gap). But that will change in 2020 in states that use HealthCare.gov, and in states with state-run exchanges that opt to implement this special enrollment period.

[It’s important to keep in mind, however, that a mid-year plan change will result in deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums resetting to $0, so this may or may not be a worthwhile change, depending on the circumstances.]

As of 2022, there will also be a special enrollment period for exchange enrollees with silver plans who have cost-sharing reductions and then experience a change in income or circumstances that make them newly ineligible for cost-sharing subsidies. This will allow people in this situation to switch to a plan at a different metal level, as the current rules limit them to picking only from among the other available silver plans.

For people already enrolled in the exchange, SEP applies if the plan substantially violates its contract

A special enrollment period is available in the exchange (only for people who are already enrolled through the exchange) if the insured is enrolled in a QHP that “substantially violated a material provision of its contract in relation to the enrollee.” This does not mean that enrollees can switch to a new plan simply because their existing carrier has done something they didn’t like – it has to be a “substantial violation” and there’s an official channel through which such claims need to proceed. It’s noteworthy that a mid-year change in the provider network or drug formulary (covered drug list) does not constitute a material violation of the contract, so enrollees are not afforded a SEP if that happens.

Who doesn’t need a qualifying event?

In some circumstances, enrollment is available year-round, without a need for a qualifying event:

-

Native Americans/Alaska Natives – as defined by the

Indian Health Care Improvement Act –

can enroll anytime during the year. Enrollment by the 15th of the month (or a later date set by a state-run exchange) will result in an effective date of the first of the following month. Native Americans/Alaska Natives may also switch from one QHP to another up to once per month (the special enrollment periods for Native Americans/Alaska Natives only apply within the exchanges – carriers selling off-exchange plans do not have to offer a monthly special enrollment period for American Indians).

-

Medicaid and CHIP enrollment are also year-round. For people who are near the threshold where Medicaid eligibility ends and exchange subsidy eligibility begins, there may be some “churning” during the year, when slight income fluctuations result in a change in eligibility.

If income increases above the Medicaid eligibility threshold, there’s a special open enrollment window triggered by loss of other coverage. Unfortunately, in states that have not expanded Medicaid, the transition between Medicaid and QHPs in the exchange is nowhere near as seamless as lawmakers intended it to be.

-

Employers can select

SHOP plans (or small group plans sold outside the exchange) year-round. But employees on those plans will have the same sort of annual open enrollment windows that applies to any employer group plans.

Need coverage at the end of the year?

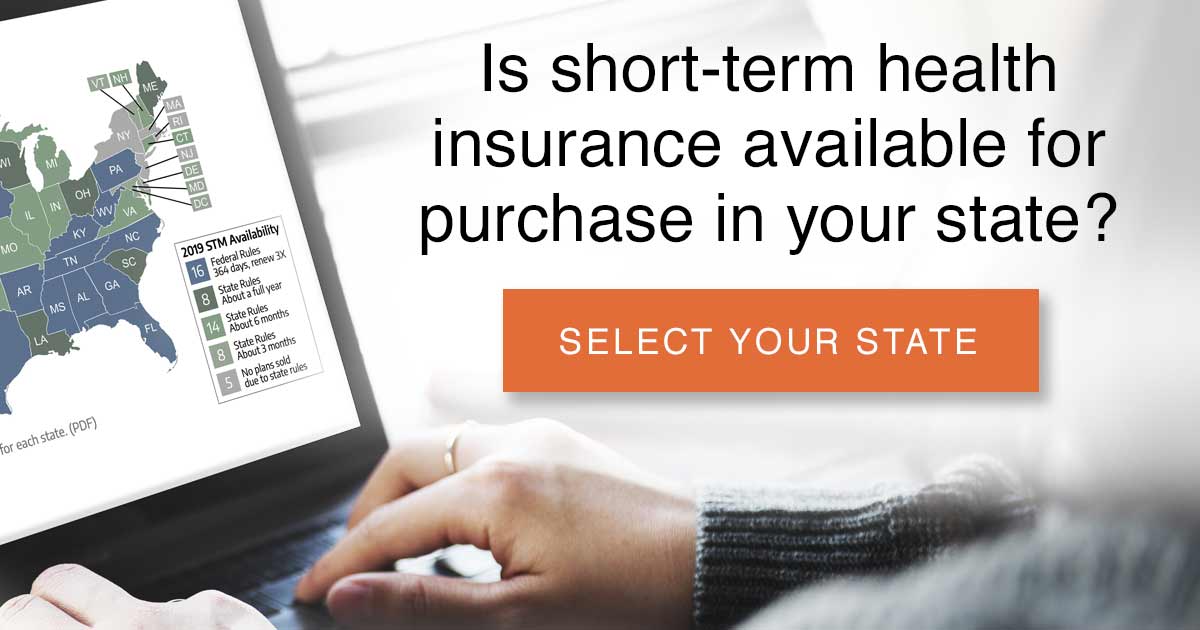

If you find yourself without health insurance towards the end of the year, you might want to consider a short-term policy instead of an ACA-compliant policy. There are pros and cons to short-term insurance, and it’s not the right choice for everyone. But for some, it’s an affordable solution to a temporary problem.

Short-term insurance doesn’t cover pre-existing conditions, so it’s really only an appropriate solution for healthy applicants. And for applicants who qualify for premium subsidies in the exchange, an ACA-compliant plan is also likely to be the best value, since there are no subsidies available to offset the cost of short-term insurance.

But if you’re healthy, don’t qualify for premium subsidies, and you find yourself without coverage for a month or two at the end of the year, a short-term plan is worth considering. You can enroll in a short-term plan for the remainder of the year, and sign up for ACA-compliant coverage during open enrollment with an effective date of January 1. The temporary health plan would certainly be better than going without coverage for the last several weeks of the year, and it would be considerably less expensive than an ACA-compliant plan for people who don’t get premium subsidies.

So for example, if your employer-sponsored coverage ends in October and you want to use a short-term plan to bridge the gap to January, that may be a good option. Be aware, however, that it may not be a good idea to drop your ACA-compliant plan and switch to a short-term plan at the end of the year, particularly if you’re in an area with limited availability of ACA-compliant plans. The market stabilization rules allow insurers to require applicants to pay any past-due premiums from the previous 12 months before being allowed to enroll in new coverage. If you receive premium subsidies and you stop paying your premiums, your insurer will ultimately terminate your plan, but the termination date will be a month after you stopped paying premiums (if you don’t get premium subsidies, your plan will terminate to the date you stopped paying for your coverage). In that case, you essentially got a month of free coverage, and the insurer is allowed to require you to pay that month’s premiums before allowing you to sign up for any of their plans during open enrollment.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org. Her state health exchange updates are regularly cited by media who cover health reform and by other health insurance experts.

The post Qualifying events that can get you coverage appeared first on healthinsurance.org.